Protections for people fleeing violence and persecution have long been written into domestic law and included in treaties signed by the U.S. government.

As a people of faith, we believe in protecting the inherent dignity of every human being, including those seeking asylum at the U.S.-Mexico border. It is not a crime to seek asylum.

BY ISN STAFF | June 22, 2019

When 100 men, women, and children who fled the war-torn African nation of the Democratic Republic of Congo arrived at the Vive Shelter, in Buffalo, New York last week looking for assistance as they seek asylum in the United States, there was a problem. The Vine Shelter, a program of Jericho Road Community Health Center on Buffalo’s East Side, had “no room in the inn.” The influx of asylum seekers had overwhelmed their facilities capacity and they were seeking assistance from the Buffalo metro community to find lodging for new and existing residents.

Canisius College in Buffalo, New York, was founded in 1870 by Jesuits from Germany and is named after St. Peter Canisius.

Those that stepped in to offer assistance include Canisius College, who will provide lodging and meals for 13 asylum seekers in a campus residence hall for three weeks beginning Sunday, June 23.

“As a Jesuit university, [Canisius College] seeks to stand in solidarity with the worldwide Society of Jesus in walking with the poor and the outcasts of the world,” said John Hurley, Canisius College president, in a message to the campus community earlier this week. “This is an opportunity to animate our mission and support the great work of Jericho Road Community Health Center.”

Hurley recently returned from a campus immersion experience to El Salvador and the U.S.-Mexico border coordinated by Christians for Peace in El Salvador (CRISPAZ) and the Kino Border Initiative. In the campus-wide e-mail announcing the initiative to host the asylum seekers he cited the experience he and his wife Maureen had meeting people during the experience, saying, “we were profoundly moved by the stories of migrants trying to escape violence to protect their families and seek a better life.”

“As a Jesuit university, [Canisius College] seeks to stand in solidarity with the worldwide Society of Jesus in walking with the poor and the outcasts of the world.”

The campus guests represent several African countries as well as Sri Lanka. Having left lives in their home countries, there is an attorney, businessmen, an information technology professional, a pastor and some who are students. Those who have work permits will spend their days at their jobs and others will return to the Jericho Road facility to assist with volunteer needs and chores.

At Hurley’s direction campus administrators developed a plan to respond to his invitation to the guests. The offices of residence life, mission and ministry, and campus ministry are working to coordinate campus facilities and daily meals for the men. Campus volunteers, including students, faculty, and staff are already responding to the invitation to assist in the preparation of a hot meal each evening as well as joining the men for dinner. Volunteers are being encouraged to consider recipes that respond to the range of diets and religious needs of each individual.

“Canisius will use this opportunity to provide hospitality and a respite to our guests,” said Sarah Signorino, the director of Canisius’ mission and identity office. “But, more importantly, we want to use this as an opportunity to build further bridges and educate around issues of migration in our community.”

“We want to use this as an opportunity to build further bridges and educate around issues of migration in our community.”

Buffalo, known as “the City of Good Neighbors,” a self-proclaimed title that represents Buffalonians welcoming spirit to those who visit or come to call the region their home. Said Signorino, “it is the duty of Canisius College to respond to those standing most on the margins.”

Asylum is a protection granted to individuals who have entered into the United States or have presented themselves the border and meet the international law definition of a “refugee.” The United Nations 1951 Convention and 1967 Protocol define a refugee as a person who is unable or unwilling to return to his or her home country, and cannot obtain protection in that country, due to past persecution or a well-founded fear of being persecuted in the future “on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.” At the end of 2017, there were approximately 3.1 million people around the world waiting for a decision on their asylum claims, according to the United Nations Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. The Trump Administration has sought to limit the ability of people to seek asylum in the U.S., especially those arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border from Central America.

Support for refugee and immigrant communities is not new to Canisius College, an ISN member institution. In 2018, the school became an active member in Ignatian Solidarity Network’s Campaign for Hospitality. Students and staff attend the annual Ignatian Family Teach-In for Justice, where they advocate for humane migration policies on Capitol Hill. In July, a Canisius student leader will participate in ISN’s Ignatian Justice Summit, a leadership formation program for students interested in advocating on immigration issues. In addition, President Hurley has expressed his support for immigrant populations, joining fellow Jesuit university presidents in signing on to a number of statements in support of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrival (DACA) students since becoming president in 2010.

[American Immigration Council, Canisius College]

Chris joined the Ignatian Solidarity Network (ISN) as executive director in 2011. He has over fifteen years of experience in social justice advocacy and leadership in Catholic education and ministry. Prior to ISN he served in multiple roles at John Carroll University, including coordinating international immersion experience and social justice education programming as an inaugural co-director of John Carroll’s Arrupe Scholars Program for Social Action. Prior to his time at John Carroll he served as a teacher and administrator at the elementary and secondary levels in Catholic Diocese of Cleveland. Chris speaks regularly at campuses and parishes about social justice education and advocacy, Jesuit mission, and a broad range of social justice issues. He currently serves on the board of directors for Christians for Peace in El Salvador (CRISPAZ). Chris earned a B.A. and M.A. from John Carroll University in University Heights, Ohio. He and his family reside in Shaker Heights, Ohio.

Chris joined the Ignatian Solidarity Network (ISN) as executive director in 2011. He has over fifteen years of experience in social justice advocacy and leadership in Catholic education and ministry. Prior to ISN he served in multiple roles at John Carroll University, including coordinating international immersion experience and social justice education programming as an inaugural co-director of John Carroll’s Arrupe Scholars Program for Social Action. Prior to his time at John Carroll he served as a teacher and administrator at the elementary and secondary levels in Catholic Diocese of Cleveland. Chris speaks regularly at campuses and parishes about social justice education and advocacy, Jesuit mission, and a broad range of social justice issues. He currently serves on the board of directors for Christians for Peace in El Salvador (CRISPAZ). Chris earned a B.A. and M.A. from John Carroll University in University Heights, Ohio. He and his family reside in Shaker Heights, Ohio.

BY LENA CHAPIN | January 21, 2019

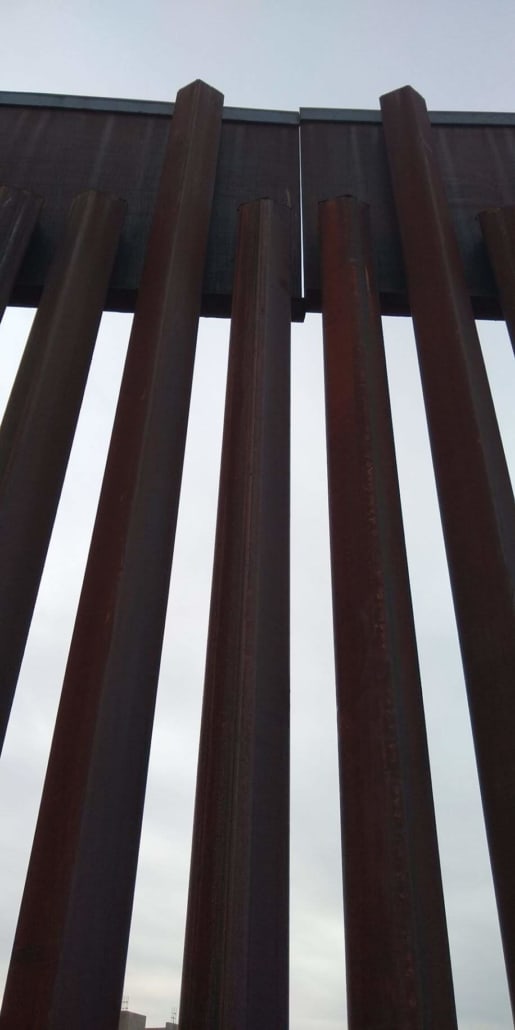

“Show me the border,” Diego Adame, Community Organizer with Hope Border Institute and our guide that morning, challenged. From high on the mountain, the city of El Paso, Texas was indistinguishable from Juarez, Mexico. We saw one continuous metropolitan area with tall buildings, highways, bridges, homes, and church towers. Even after he pointed it out, the wall was difficult to find and easy to lose track of. So we drove down the mountain into the side streets of Sunland Park, New Mexico, crossed some railroad tracks, and parked in the sand near the tall metal planks reaching skyward. Three border patrol vehicles shifted nearby.

The U.S.-Mexico border from Las Cruces, New Mexico.

Here was this wall. The wall that I had come to see. The wall that is creating so much pain and discourse across the U.S. That wall, those slabs of metal are the division… right?

Soon, two men approached on the other side of the fence. We started exchanging morning pleasantries, talking about how cold it was outside, joking about the displeasure of having to go to work. They wished us well on our journey to learn more about the border and headed off to start their days. It struck me as we circled up for prayer how typical the conversation was. It would have been almost the exact conversation had we been in line at the grocery store, but instead, there was an 18-foot steel wall constructed between us.

Immersion participants chatting with local residents through the border wall.

Later that day we would drive over the bridges into Juarez and visit with people living in the neighborhood of Anapra, feeling welcome, hospitality, and warmth. We came back across, joking with street vendors and tallying up the different license plates going through the border checks fairly easily. Throughout the week, everyone we spoke with living in the tri-state area (Chihuahua, New Mexico, and Texas) had similar sentiments: “ I was born in ________, but I live in _____________ and I work in ______________.” The cities were almost interchangeable. Many people travel frequently—sometimes even daily— between these three states and two countries. And everyone we met was working to improve their community.

Returning to the U.S. from Ciudad, Juarez.

As the week continued, the wall moved into the background of my thoughts. Even as the President was declaring a national crisis and continuing to use it as a divisive measure within the interior, those at the border went about their lives.

On Friday morning we heard a presentation from Dylan Corbett, director of Hope Border Institute, that best embodied the phenomenon I was feeling regarding the wall:

“When I consume the Eucharist, I am not consuming anything. Rather, I am being consumed. Christ is bringing me into a relationship with everybody. St. Paul said ‘Once I am brought in I can no longer say to the foot, I can no longer say to a person, I do not care about you.’ If it’s true that Christ, that God, is bringing us into deeper relationship with everybody, that He is creating something, He is acting through history, He is bringing about the birth of something new, the body of Christ—and the Eucharist is about that, feeding that, nourishing that, growing that— then you have to ask the question at the end of the day: what is really real? Is that wall really real?”

It certainly didn’t feel real later that day as we celebrated Mass at a detention center, sharing in the Eucharist with hundreds of men and women from around the world. As we entered into communion with these men and women and shared signs of peace and brief conversations, internal and external borders faded into the background. We were Christians, family, one body of Christ.

I had the same feeling at the shelter for folks seeking asylum who had been released by ICE. There weren’t divisions just because they had passed through the wall or crossed a borderline. There was no “us” and “them.” There were simply parents sharing understanding glances as children made messes out of cookies and juice. There were weary travelers appreciative of clean sheets and the promise of a good night sleep.

The whole concept of borders was challenged as I learned more about the history of the area; the trade routes, how these Native lands became part of Mexico, then the U.S., and even then, borders shifted between New Mexico and Texas.

But the wall is real. Structurally, destructively. This wall that doesn’t seem real even after seeing it and touching it is being used as a pawn to actively oppose the work of the Eucharist, the work of God. It is dividing the U.S. internally through opinions and beliefs. It has caused thousands of people in the interior of the U.S. to go without paychecks, which means many of them are going without food. And it is continuing to be a physical representation of the idea that some deserve to have the freedoms that the United States offers and that others do not.

It’s been said by many advocates for justice that problems at the margins are because of exploitation and lack of knowledge from those in positions of privilege. Faith leaders for centuries have called us “to go to the margins.” There seems to be a pattern here…it is only through encounter that walls fall away. I know mine did.

Lena Chapin is the development director for Edwins Leadership and Restaurant Institute in Cleveland, Ohio. After graduating from John Carroll University, she spent a year in Immokalee, Florida with the Humility of Mary Volunteer Service. Lena worked for the Ignatian Solidarity Network from 2016-2022.

BY KEVIN TUERFF | October 18, 2018

Imagine if someone kidnapped you, and then threatened to murder you. You escape, but you have no support from police to protect you. Wouldn’t you flee to save your own life?

If this happened to you, and you managed to get a visa to the U.S., and you declared asylum at JFK airport—you are then shackled and handcuffed. Your luggage is taken from you and you are forced to wear a blue prison jumpsuit. You are taken to corporate-run jail for at least six months while you await a hearing from an immigration judge. Inside, you are offered food which is often inedible. You have little access to medical care. If you are lucky, you have volunteers from a church who accompany you in detention, coming weekly for a one-hour visit. If you are lucky, you have help from a pro-bono attorney, otherwise you will likely be deported, sent back into harm’s way.

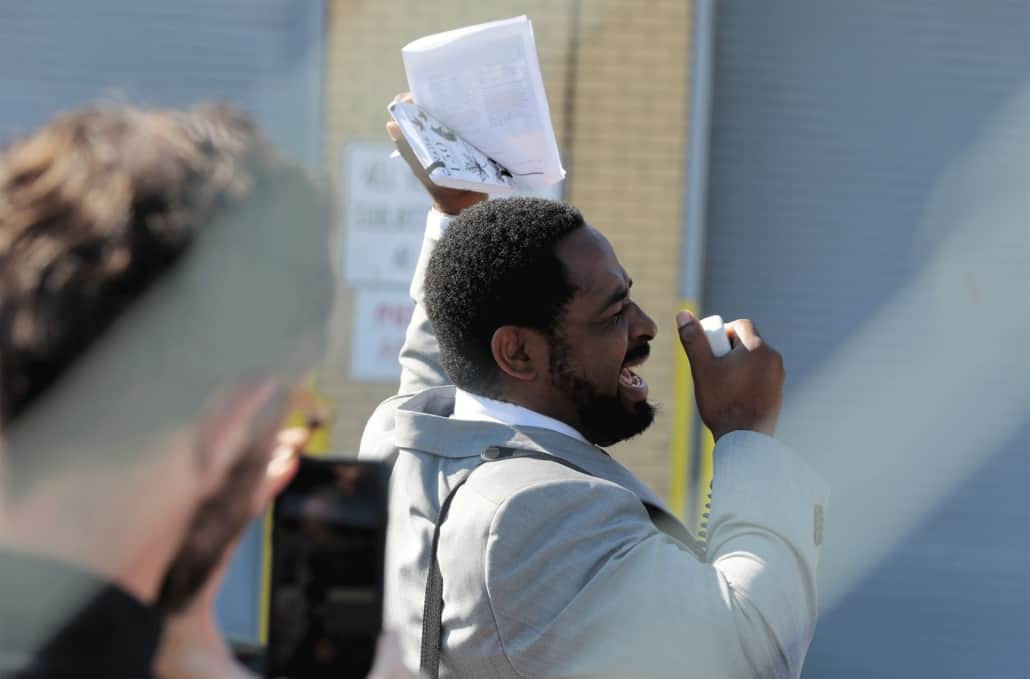

If you are granted asylum, and you are freed from this nightmare, would you return to the detention center soon thereafter to join a prayer vigil and visit other detainees? Sam, a new refugee from West Africa did just that on Sunday, September 16 in Elizabeth, New Jersey. He shared his stories of the terrible conditions in detention, and also led the group in a prayer for the 400 detainees inside who are seeking freedom in the United States.

Sam, a new American who was granted asylum after spending 7 months inside the Elizabeth, NJ immigration detention center, joined the group to pray for his former detainees who remained inside the corporate-run jail. [Photo by Donald Kennedy]

When one of the guards at the Center came outside to dissuade the group from getting close, Sam went and shook hands with his former captor. It was a powerful moment.

More than 100 Catholics walked the 30-minute journey through a Newark, NJ warehouse district, from the nearest bus stop to Elizabeth Detention Center. [Photo by Donald Kennedy]

The group walked two-by-two for more than 30 minutes in the heat from the nearest transit stop, past a maze of distribution warehouses, to the corporate-run detention center. When detainees are granted asylum there, they are usually set free in the middle of the night with no assistance to find public transportation to a refugee shelter.

Teresa Carino, pastoral associate at St. Ignatius Church in New York City spoke outside Elizabeth Detention Center. [Photo by Donald Kennedy]

Fr. Daniel Corrou, S.J., acting pastor of Church of St. Francis Xavier (New York City) led the pilgrims in prayers for the hundreds of women and men inside the immigration detention center. [Photo by Donald Kennedy]

Recent news reports have shed light on the horrific plight of migrant children also being held in detention, separated from their parents. Christ calls us to pray, and advocate for humane policy changes with Immigration Customs Enforcement.

Kevin Tuerff is a social entrepreneur, author and speaker. He is passionate about finding solutions for climate change and refugees. Kevin’s hometown is New York City where he is a member of the Church of St. Francis Xavier. His true story of being an American 9/11 refugee is portrayed in the Broadway musical COME FROM AWAY, and in his memoir, “Channel of Peace: Stranded in Gander on 9/11.” He is also an ambassador for Charter for Compassion International. Follow him on Twitter @channelof_peace.

BY VINCE HERBERHOLT | September 19, 2018 | EN ESPAÑOL

Two Jesuit parishes in the Pacific Northwest, St. Joseph Seattle and St. Leo Tacoma, joined together to coordinate a pilgrimage and Mass at the GEO-run Northwest Immigrant Detention Center on Saturday, August 25, 2018. More than 500 faith-filled pilgrims prayed and sang for 1.6 miles from St. Leo to the Center where over 1,500 detainees are imprisoned while waiting for immigration hearings or deportation.

St. Joseph Parish members participate in the pilgrimage.

Frs. John Whitney, S.J., and Matt Holland S.J., pastors of St. Joseph and St. Leo respectively, concelebrated the Mass. Fr. Scott Santarosa, S.J., the provincial of the Jesuit West province delivered the homily, exhorting the pilgrims to “bridge all divides, and foster understanding among diverse peoples and cultures, and make people feel in the most real way at home.”

(L-R) Fr. Scott Santarosa, S.J., Fr. John Whitney, S.J., and Fr. Matt Holland, S.J. celebrate Mass outside of the Northwest Immigrant Detention Center on Saturday, August 25, 2018.

During the event, signatures were collected on a petition for the reform of immigration policies in the United States, which will be delivered to local congressional offices. The event renewed energy for continuing work on behalf of immigrants and refugees.

Mass and pilgrimage participants share a meal after the event.

However, even more inspiring were the connections made with the help of the Ignatian Solidarity Network. Over 18 Jesuit parishes and works across the U.S. joined in the group of pilgrims in prayer or with their own activities. In the Jesuits West province that included St. Aloysius in Spokane, St. Ignatius in Portland, St. Ignatius in Sacramento and San Francisco, St. Agnes in San Francisco, Dolores Mission in Los Angeles, St. Francis Xavier in Missoula, the Intercommunity Peace and Justice Center in Seattle, the Ignatian Spirituality Center in Seattle, and the Kino Border Initiative in Nogales, Arizona and Sonora, Mexico.

A Campaign for Hospitality banner outside the Northwest Immigrant Detention Center. St. Joseph Parish is a Campaign for Hospitality member institution.

Parishes in other parts of the country include St. Francis Xavier in St. Louis, Bellarmine Chapel at Xavier University in Cincinnati, Church of the Gesu in University Heights, OH, St. Francis Xavier and St. Ignatius in New York City, St. Ignatius in Chestnut Hill, MA, Holy Trinity in Washington D.C., St. Ignatius in Baltimore, and St. Thomas More in Atlanta.

Five of these parishes will be leading their own pilgrimage and Mass or prayer service at detention centers in their area: St. Ignatius in Chestnut Hill, MA, Holy Trinity in Washington D.C. and St. Ignatius in Baltimore, and St. Francis Xavier and St. Ignatius in New York City.

All the Jesuit parishes and works that have joined in this endeavor have expressed interest in continuing collaborations related to immigration reform. Knowing that there is more important work to be done, an ongoing discussion will continue through the Jesuit Parish Collaboration Framework. The Ignatian Solidarity Network designed the initiative to deepen Jesuit parish connection to the Ignatian network by engaging in discernment, action, and advocacy as a parish network.

Vince served the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services for 32 years, retiring as an Associate Regional Administrator in 2007. After retiring, Vince completed a master’s degree in pastoral studies at Seattle University. He served on the board of JustFaith Ministries for 8 years and currently serves on the board of the Ignatian Spirituality Center, where he helps to coordinate the Men’s Spirituality program. Vince is a member of St. Joseph Parish, the Jesuit Parish in Seattle. He has been married to Cathy Murray for 41 years. They have 2 adult sons, Bernard and Conrad.

BY LIZZIE HUDSON | September 19, 2018

When I was in fourth grade, I learned about immigration for the first time. I remember my teacher telling us about Ellis Island and all the people that came into our country looking for a better life.

She spoke about European immigrants as a simple matter of fact. Then she used a term that I will never forget: illegal alien. She used it to describe people who crossed the U.S.-Mexico border illegally. My ten-year-old self didn’t understand why she would use positive sounding words for one group of immigrants but not for the other.

An 18-foot border wall in Sunland Park, New Mexico, built near the end of the Obama Administration.

Fast forward to this past summer, to the days leading up to my border awareness trip with the Columban Mission Center in El Paso, as I was trying to figure out how I felt about going.

Was I nervous? No.

Was I excited? That didn’t quite describe my feelings.

I was just ready—ready to start the journey. This would be my first time on the border. I had only seen what it was like through the news and textbooks. I knew that I would be meeting immigrants who had just made it to the United States. While listening to their stories, I expected I would have to hold back tears. I couldn’t have been more wrong.

During one of the days, my group was asked to cook a meal for the guests staying at Annunciation House, a local shelter for migrants. We decided to make enough eggplant and chicken parmesan (and watermelon for dessert) for forty people. We chopped vegetables, tenderized chicken, and sliced bread for hours.

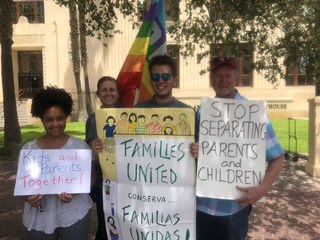

At the El Paso courthouse protesting family separation at the U.S.-Mexico border.

Even with my whole group working on this task, I was tired when we finished. But then our guests started to arrive. We greeted everyone in broken Spanish. Once everyone got their food and sat down, I was immediately drawn to a table with children.

I love kids, and I have a niece back home who I was missing. Sitting at the table was their mother, a teenage girl, and Jorge, who is the same age as me. I don’t speak much Spanish and they didn’t speak much English. But instead awkward silences I expected, the girls and I ended up making goofy faces at each other.

We went back and forth seeing who could cross their eyes and touch their tongue to their nose. They were very good at crossing their eyes! I noticed that one of the girls had the Disney princess Anna on her shirt. I showed them the Disney emoji app on my phone, and then we started imitating all of the silly faces the emojis were making.

At the farm workers center in El Paso, learning about the harsh working conditions experienced by farm workers on a daily basis.

While the girls were occupied with the Disney app, Fr. Bob (a Columban priest and the Director of the Columban Mission Center) came over to the table and started talking to their mother in Spanish. I tried to listen to their conversation but the youngest girl kept tapping my face so I would pay attention to her. I gladly obliged. We continued to make faces and laugh together until they left to return to Annunciation House.

Now it was just me, Fr. Bob, and Jorge at the table. As Fr. Bob and Jorge started talking, he shared with us why he left his home in El Salvador. Jorge is an openly gay man. When he came out to his father, his father disowned him. His father literally removed his last name from Jorge’s name.

Without his family anymore, it was just Jorge and his boyfriend. They received death threats and were victims of violence, just for being in a relationship. One of their gay friends was beheaded. So they made the decision to flee together.

When they arrived at the U.S. border, they applied for asylum and were put in detention. In the detention center, the other migrants harassed Jorge and his boyfriend. They asked the guards for help but they turned a blind eye. He told us that he had thoughts of taking his own life because of all the pain he’d suffered.

After eight months in detention, Jorge was granted asylum. Unfortunately, his boyfriend is still inside.

When Jorge told us all this, I asked Fr. Bob to translate for me: “I’m glad you’re still here.” Fr. Bob asked him how is it that he’s able to share his story with such courage and openness. Jorge said that it’s simply by the grace of God, and that whenever he feels like crying he dances instead. Fr. Bob asked him what his favorite type of dance music is (bachata), then put some on. Jorge asked me if I would dance with him. Everyone else from my group joined in the dancing too.

Speaking with residents of the neighborhood of Duranguito about their efforts to combat neighborhood destruction to build a brand new baseball stadium.

As an advocate, it’s easy for me to get caught up in the process of passing bills or organizing rallies in order to make a systemic change. But being immersed in a border community like El Paso and forming relationships with individuals made me realize that I can forget about how there are people who need help right now.

Though I like to focus my energies on working for social justice, during my time at the border I was able to focus on charitable works. I met a lot of people there who weren’t as focused on systemic change as I am. They just want to be looked at as a human being, to have somewhere to eat and sleep.

El Paso opened my eyes to the importance of balance, that social justice and charitable works go together. Many people call this the “two feet of love in action.” So my goal for this fall semester back in Omaha is to make sure I’m walking with two feet, not one.

To learn more about the border and how you can stand in solidarity with your sisters and brothers who live there, consider signing up to receive a free copy of the Columban Center’s “Border Solidarity Toolkit.” It includes a number of activities for prayer, education, and action then can help you walk with both feet of love.

Lizzie Hudson was the Environmental Justice Intern for the Columban Center for Advocacy and Outreach in the summer of 2018. She attends Creighton University, where she is studying sociology and philosophy. After graduation, Lizzie plans to go into advocacy full time—hopefully in the realms of racial justice, immigration, environmental justice or somehow a mixture of all three!

BY ISN STAFF | August 30, 2018 | EN ESPAÑOL

This summer, three Jesuits in formation arrived in El Paso at an unexpectedly crucial time.

From July 17-26, Nazareth Shelter, one of several church-based, all-volunteer temporary shelters coordinated by Annunciation House, a forty-year-old organization committed to serving recent arrivals at the U.S.-Mexico border, took on a temporary mission—receiving reunited parents and children who had been separated by the Trump Administration’s “zero-tolerance” policy.

Rafael Garcia, S.J., associate pastor at Sacred Heart, the Jesuit parish in El Paso, with Conan Rainwater, S.J., Matt Cortese, S.J., and Matthew Baugh, S.J.

Conan Rainwater, S.J. (Jesuits Midwest Province), who served as temporary shelter director, coordinating volunteer shifts and meal groups, among other logistics, was joined by Matthew Baugh, S.J. (Jesuits Central and Southern Province) and Matt Cortese, S.J. (Jesuits Northeast Province).

They joined an extensive network of volunteers tasked with providing food, shelter, and basic material needs, in addition to helping families connect with family members in the U.S., coordinating travel plans, and providing transportation and accompaniment into the airport or bus station for families who were dropped off unannounced through the day and nighttime hours.

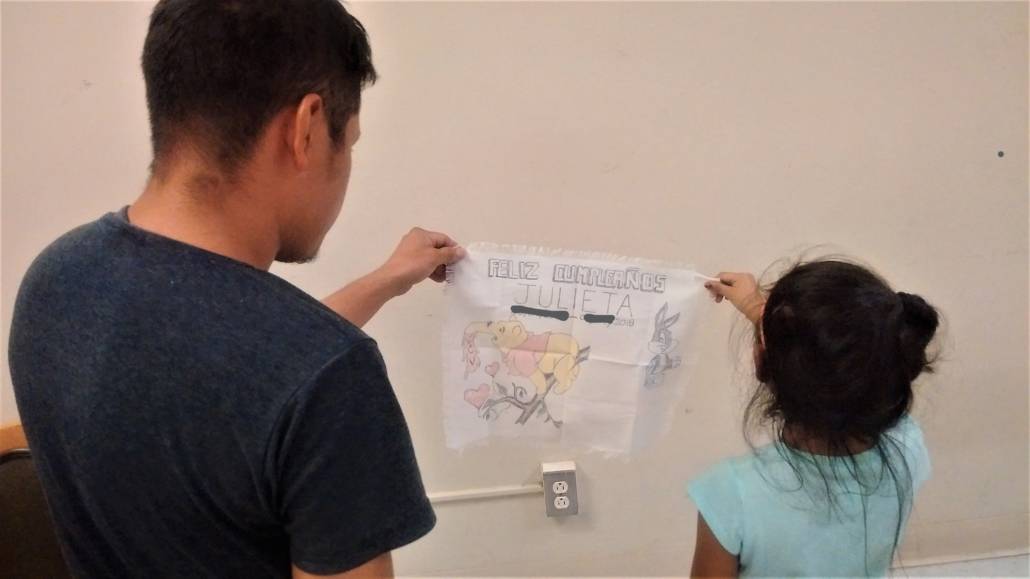

A reunified father and his nine-year-old daughter at Nazareth Shelter. The two were separated for 2 months, during which time she had a birthday. While in detention, he painted a birthday card for her. He gave her the painting on the day of reunification.

“Rather than coming in [to shelters] all at one time in a bus or two, as is the typical case for parents and minor children who are processed and released with ankle bracelets on the parents, the families came in small numbers in vans throughout the day and night,” shared Rafael Garcia, S.J., who serves migrant and refugee persons and is Associate Pastor at Sacred Heart, a Jesuit parish in El Paso, which is a member of the Campaign for Hospitality.

“This created chaos and stress for volunteers who don’t have information to plan in advance for the number of meals or volunteers needed at any given time. Conan, Matthew, and Matt were an invaluable support at Nazareth Shelter during this critical time.”

Interesting links

Here are some interesting links for you! Enjoy your stay :)Pages

- About

- Campaña por la Hospitalidad — Español

- Come to the Table Potlucks

- Events

- Feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Français – Campagne pour l’hospitalité

- Hacer el compromiso: Quédate con los que buscan asilo

- Homepage

- Immigration Detention Center Pilgrimages

- Join The Campaign

- Light in the Darkness: Uniting in Prayer for Immigrant Families

- Light in the Darkness: Vigil for Immigrant Families

- Love Your Neighbor

- News

- Resources

- Send a Love Your Neighbor Note

- Share the love – Spread the word!

- Stories

- Take Action

- Take the Pledge: Stand With Those Seeking Asylum

- Thank you for taking the pledge