BY LENA CHAPIN | January 21, 2019

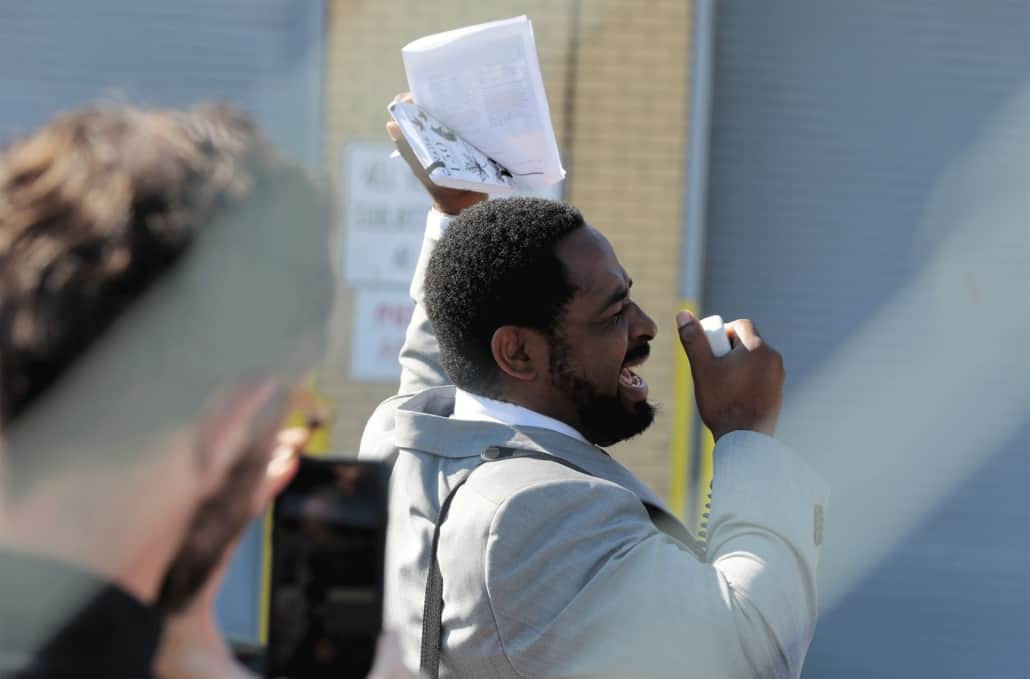

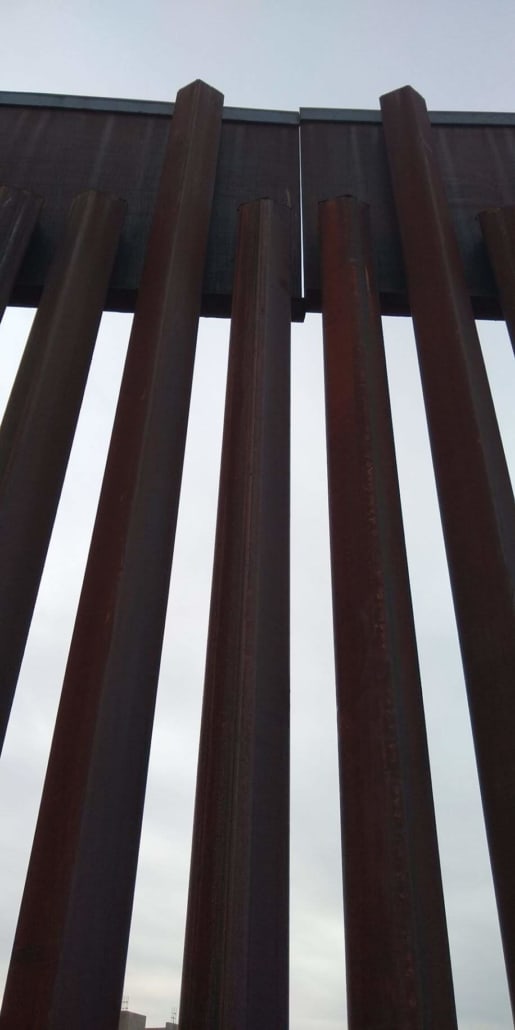

“Show me the border,” Diego Adame, Community Organizer with Hope Border Institute and our guide that morning, challenged. From high on the mountain, the city of El Paso, Texas was indistinguishable from Juarez, Mexico. We saw one continuous metropolitan area with tall buildings, highways, bridges, homes, and church towers. Even after he pointed it out, the wall was difficult to find and easy to lose track of. So we drove down the mountain into the side streets of Sunland Park, New Mexico, crossed some railroad tracks, and parked in the sand near the tall metal planks reaching skyward. Three border patrol vehicles shifted nearby.

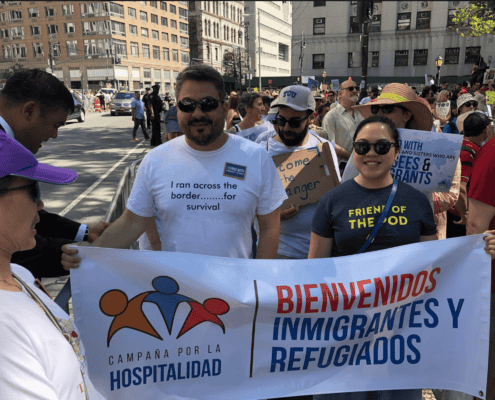

The U.S.-Mexico border from Las Cruces, New Mexico.

Here was this wall. The wall that I had come to see. The wall that is creating so much pain and discourse across the U.S. That wall, those slabs of metal are the division… right?

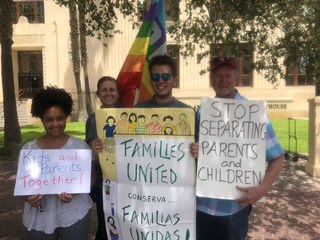

Soon, two men approached on the other side of the fence. We started exchanging morning pleasantries, talking about how cold it was outside, joking about the displeasure of having to go to work. They wished us well on our journey to learn more about the border and headed off to start their days. It struck me as we circled up for prayer how typical the conversation was. It would have been almost the exact conversation had we been in line at the grocery store, but instead, there was an 18-foot steel wall constructed between us.

Immersion participants chatting with local residents through the border wall.

Later that day we would drive over the bridges into Juarez and visit with people living in the neighborhood of Anapra, feeling welcome, hospitality, and warmth. We came back across, joking with street vendors and tallying up the different license plates going through the border checks fairly easily. Throughout the week, everyone we spoke with living in the tri-state area (Chihuahua, New Mexico, and Texas) had similar sentiments: “ I was born in ________, but I live in _____________ and I work in ______________.” The cities were almost interchangeable. Many people travel frequently—sometimes even daily— between these three states and two countries. And everyone we met was working to improve their community.

Returning to the U.S. from Ciudad, Juarez.

As the week continued, the wall moved into the background of my thoughts. Even as the President was declaring a national crisis and continuing to use it as a divisive measure within the interior, those at the border went about their lives.

On Friday morning we heard a presentation from Dylan Corbett, director of Hope Border Institute, that best embodied the phenomenon I was feeling regarding the wall:

“When I consume the Eucharist, I am not consuming anything. Rather, I am being consumed. Christ is bringing me into a relationship with everybody. St. Paul said ‘Once I am brought in I can no longer say to the foot, I can no longer say to a person, I do not care about you.’ If it’s true that Christ, that God, is bringing us into deeper relationship with everybody, that He is creating something, He is acting through history, He is bringing about the birth of something new, the body of Christ—and the Eucharist is about that, feeding that, nourishing that, growing that— then you have to ask the question at the end of the day: what is really real? Is that wall really real?”

It certainly didn’t feel real later that day as we celebrated Mass at a detention center, sharing in the Eucharist with hundreds of men and women from around the world. As we entered into communion with these men and women and shared signs of peace and brief conversations, internal and external borders faded into the background. We were Christians, family, one body of Christ.

I had the same feeling at the shelter for folks seeking asylum who had been released by ICE. There weren’t divisions just because they had passed through the wall or crossed a borderline. There was no “us” and “them.” There were simply parents sharing understanding glances as children made messes out of cookies and juice. There were weary travelers appreciative of clean sheets and the promise of a good night sleep.

The whole concept of borders was challenged as I learned more about the history of the area; the trade routes, how these Native lands became part of Mexico, then the U.S., and even then, borders shifted between New Mexico and Texas.

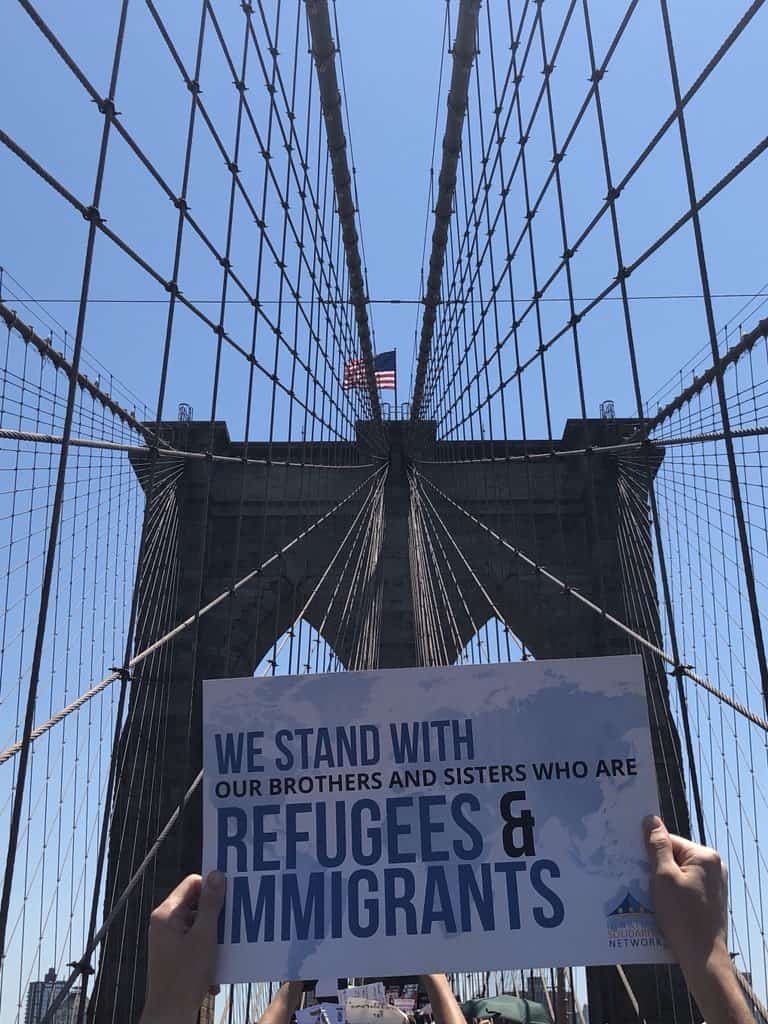

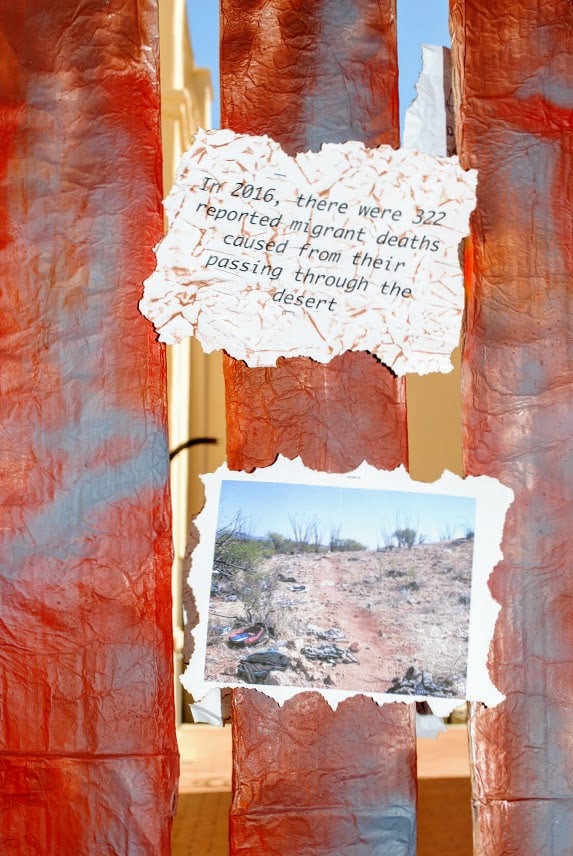

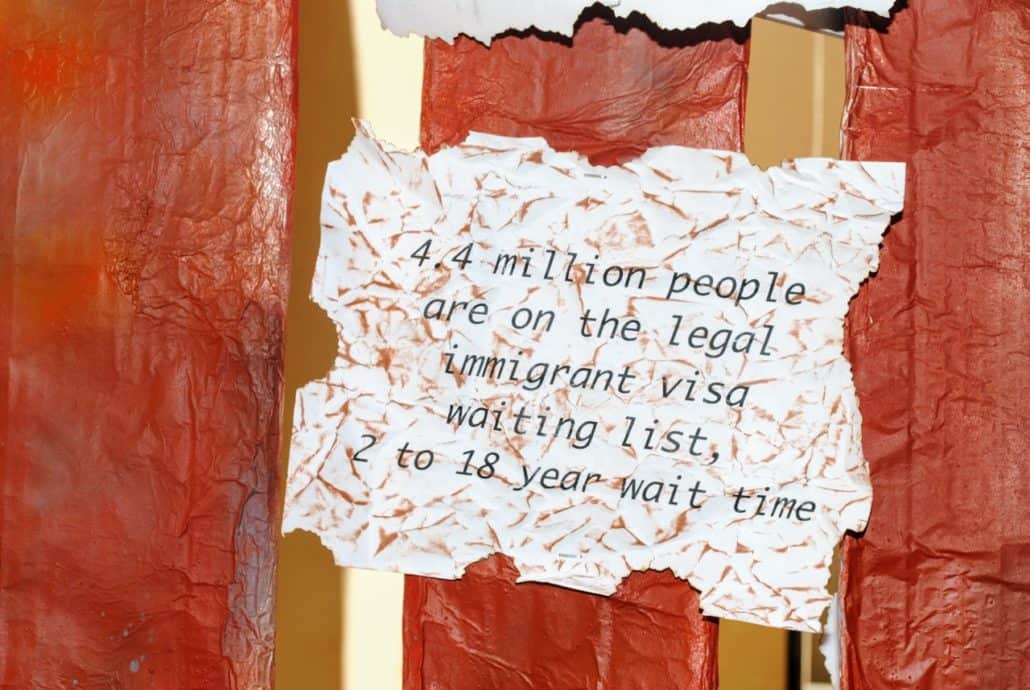

But the wall is real. Structurally, destructively. This wall that doesn’t seem real even after seeing it and touching it is being used as a pawn to actively oppose the work of the Eucharist, the work of God. It is dividing the U.S. internally through opinions and beliefs. It has caused thousands of people in the interior of the U.S. to go without paychecks, which means many of them are going without food. And it is continuing to be a physical representation of the idea that some deserve to have the freedoms that the United States offers and that others do not.

It’s been said by many advocates for justice that problems at the margins are because of exploitation and lack of knowledge from those in positions of privilege. Faith leaders for centuries have called us “to go to the margins.” There seems to be a pattern here…it is only through encounter that walls fall away. I know mine did.

Lena Chapin is the development director for Edwins Leadership and Restaurant Institute in Cleveland, Ohio. After graduating from John Carroll University, she spent a year in Immokalee, Florida with the Humility of Mary Volunteer Service. Lena worked for the Ignatian Solidarity Network from 2016-2022.